Is Academic Acceleration Leaving Peer Review in the Dust?

How an archaic peer review system is struggling to keep up in a world of for profit academic publishing.

By Adam Finnemann

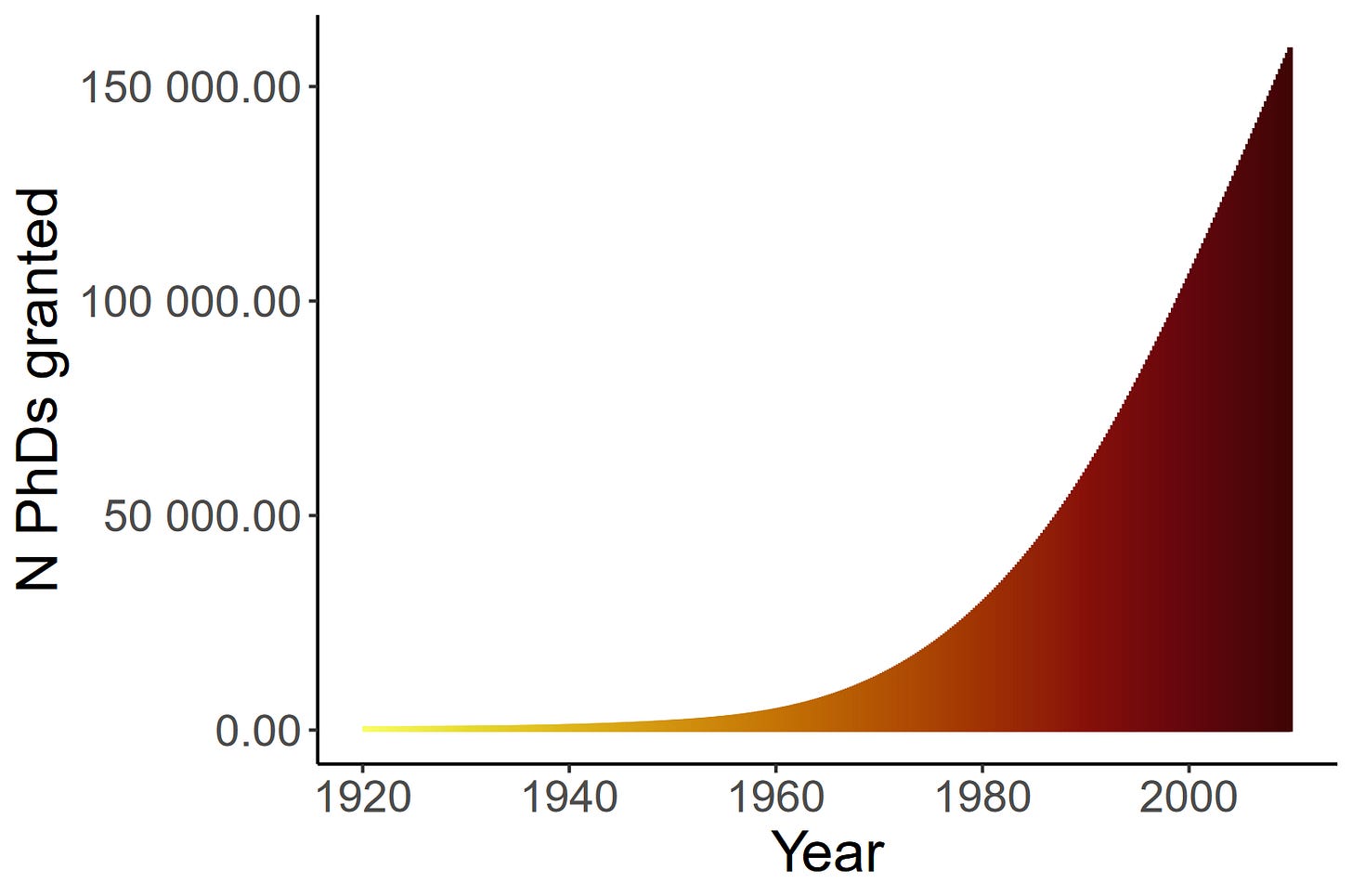

Academics are supposedly reasonable people, so one might expect that academia is set up as a reasonable system. Sadly, this is not so. In the words of Deutsche Bank, academic science has grown into a bizarre triple pay system where publishers of academic journals have lured the public into paying them while academics do the hard work. Surprisingly, an exponentially increasing amount of people accept these working conditions – myself included. Consequently, we also see exponential growth in scientific output.

The first part of this blog seeks to explain what drives this exponential growth while the second half discusses some looming problems caused by the rapid expansion of science. More concretely, we’ll see how it benefits the pockets of publishers and egos of academics but also creates a systemic threat to our central epistemic safeguard, peer review.

The commercial interest in publishing more

To understand the exponential growth, we start our academic tour with the rise of commercial publishing.1 The cold war’s arms and space race made science and technology a political priority. Consequently, governments increased their spending on universities and their libraries which became rich.

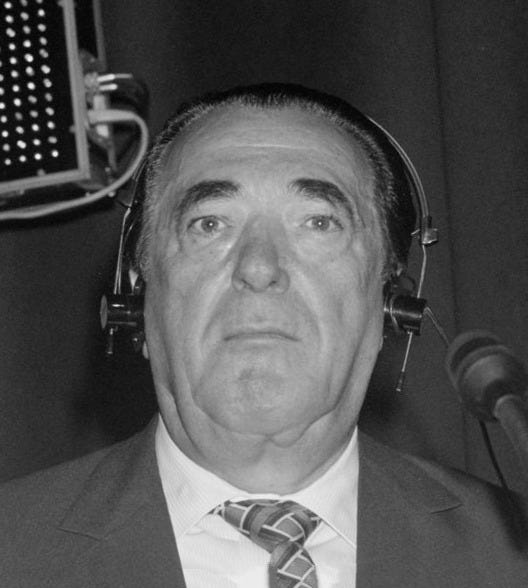

These new gold mines were eyed by the notorious business tycoon, Robert Maxwell, who was tasked by the UK government with speeding up scientific publishing. Something he accomplished through the invention of commercial academic publishing.

Maxwell used his flair for marketing and persuasion to convince and manipulate respected academics to spearhead his newly founded journals. The trick was to bring lavish dinners and high-society vibes into the lives of the academics (Here there is an uncanny resemblance to how his daughter, Ghislaine Maxwell, and Jeffrey Epstein exploited underage girls). With leading figures onboard, Maxwell’s journals gained academic credibility. This eased the process of convincing well-funded libraries to subscribe to his journals.

Revenue came from these subscription fees, which could be raised in two ways. More journals meant more subscriptions, and more publications per journal justified increased subscription fees. Maxwell pushed both levers with great success. In 1959 he had 40 journals to his name, a number which grew to 150 by 1965. Scaling journals and publications was easy as Maxwell’s business model kept costs unbelievably low and profits high.

We can illustrate the business model with the following scenario. Imagine being a tomato farmer, growing your tomatoes on a small farm. One day a stranger approaches. She offers to judge the quality of your tomatoes and distribute them globally if they are sufficiently good, however, you will need to give your tomatoes to the stranger for free. You like the idea of global outreach and making a name for yourself, so you accept. The next day the same stranger returns. Now she is looking for a tomato expert to judge the quality of tomatoes on a voluntary basis. After all, you are one of few tomato experts, so you agree to quality check her tomatoes for free. After a while, the stranger returns offering you to buy these, according to experts, world-class tomatoes. Not having any tomatoes, you accept her offer. That is, you have been sold the tomatoes which you have grown and quality checked yourself.

In reality, no farmer would act this foolishly. But what about academics? If we replace the tomato farmer with academics and the stranger with Elsevier or another publishing house, then we have the business model of academic publishing.

It is a bizarre triple-pay system where academics give their materials and rights for free, and voluntarily quality check them, before the universities buy subscriptions to access the material.

Things get even worse when we look at the prices of subscriptions. In the last decade, subscription fees increased 5% per year implying that costs double in 14 years. This is despite publishing costs remaining constant and inflation levels around 1 to 2 % in that period. This trend is not just found in journals, but also in academic books. For instance, Elsevier offers their 2nd edition of Comprehensive Clinical Psychology in hardcover + eBook at 9,600 EUR. Yes, it’s just a book. But then you also have 4800 pages to enjoy while you save - remember the 5% annual increments - for the next edition.

With astronomical prices and increments, it is no wonder that the publishing industry is one of the most profitable in the world. The big publishers generally post 30+ % profit margins, and RELX, the new fancy name of Elsevier-rex, has seen a 460% stock price increase (500£ to 2,300£) since 2012.

Although some university libraries are trying to cut ties with publishers, they cannot refuse the publishers’ terms without harming their research. The conditions under which academics give their articles to publishers are such that the publishers own all rights. This means that in most countries, researchers aren’t allowed to have copies of their work on their websites as this infringes on the monopoly rights of the publishers. A recent remedy is open-access publishing, where manuscripts are published such that it’s accessible without a subscription. This benefits the general public who can now access the scientific literature, which was funded by their taxes in the first place. The caveat here is that researchers then pay to publish, and these fees are astronomical. A recent meme-spurring Nature neuroscience tweet announced that this year's fee for publishing open access is 9,500 EUR.

It’s clear that the publishing houses have incentives to scale this enormously profitable system, as more publications mean more money. What’s less clear is why academics do not object more strongly to the system.

Why do academics participate in the system?

There is a crucial difference between our analogy between the farmer and the academic system. Whereas tomato farmers are self-paid, academia is mostly funded by taxpayers through governments. This means that academics don’t pay 10,000 EUR for books and publication fees out of their own pocket. They redirect the bills to publicly funded university bank accounts. Thus, academics don’t feel ownership over the money which makes them care less about the insanely high prices they pay. Furthermore, in return for the high prices academics get something they care about: outreach, attention, and prestige.

These currencies of the egos are provided by the rise of quantitative proxies of quality — h-index, citation counts, publication counts, and impact factors. They effectively allow researchers to compare themselves to others and replace the abstract question of “am I doing good and impactful science” with specific quantities and social comparisons.

The exponential growth of science requires these quantitative summaries. With numerous candidates for open positions, tenure, conference talks, publications, grants, and applications it is not feasible to do a case-by-case assessment. This bottleneck is solved by sorting candidates based on number of citations, number of publications, and impact factors of journals.

Since key decisions are determined by these proxies, academics can game the scientific system by optimizing them. Thus, the proxies align academics’ interests with those of publishers: publishing more. I think this agreement between individual and structural interests ultimately explains the observed exponential trajectory in publications, even though they might have detrimental social costs.

Peer-reviewing academic publishing: a major revision

It’s not only publications and publishing fees that are growing. There are also growing problems facing peer review. This is the process where experts review manuscripts to ensure only quality research is accepted into the literature that guides our policies, education, public health, climate rescue, you, and your doctor. Thus, its quality is central to ensure from a public and government perspective. The absurdity is that while taxpayer money funds 10,000 EUR books, it does not directly fund peer review as it works on a voluntary basis. Journal editors ask reviewers to review manuscripts that fall within their expertise. There is a small incentive to review for good journals since it looks good on CVs. However, this incentive fades after the first reviews. More problematically, there is no incentive to do the job well or costs to reviewing poorly. A similar problem occurs in the recruitment process. Editorial roles are voluntary positions, except in the top journals. Finding relevant experts is central for quality reviews, however, in the current system, there are few incentives to do this properly and costs to do this poorly. A comical result of this is the stories of authors accidentally invited to review their own papers.

The crux of the problem is that peer reviewing is an incredibly difficult task. Articles are complex structures involving many parts – literature review, data, code, analysis, research question, visualization, interpretation, discussions, conclusions, etc. Reviewers differ in background and competences and consequently in how evaluations of the parts are integrated into an overall accept/reject/revise decision.

The complexity and difficulty lead to disagreement in the review process. Studies have empirically shown disagreement in overall rejection and acceptance decisions (Cicchetti, 1991; Siler, Lee, & Bero, 2014, Wood, 2003). A central cause is that reviewers do not catch errors reliably. Three studies found that only 25%, 29%, and 30% of intentional flaws and errors were caught by reviewers. This shows that spotting errors is difficult. Because of this difficulty, reviewers are encouraged to use problematic heuristics. A recent study showed that the same manuscript will receive different judgments depending on the prestige of the authors’ university. 534 experts reviewed the same manuscript but either saw high or low-status affiliations. When author universities had low status the direct acceptance and reject rates were 2% and 65% respectively. For the high-status institution condition, the direct acceptance grew to 20% while direct rejection rates fell to 22%.

The low reliability of peer review induces luck in the process. Academics can capitalize on this by submitting their manuscript until they hit the jackpot – getting kind reviewers on their good days. In turn, academics are losing faith in the reviewing system. My evidence for this is the rise of pre-print and working papers. Over the past decade, uploading a manuscript to an archive prior to the peer review process has become common practice. The striking development is that it’s unproblematic to cite pre-prints in articles as if they were peer-reviewed. I interpret this as academics not holding peer review in high esteem but rather trusting their own judgment of the pre-print or the author of it. A practice that might not be so problematic as long as they are experts on the topic. The practice of citing pre-prints is also due to peer review being super slow. Years can pass from submission to publication which creates a problem when follow-up papers are written within that timeframe.

A systemic challenge to peer-review

The previous arguments raise the question: why does peer review persist? The first part of the answer is found in academics caring about knowledge and acknowledging the societal need for peer review. These honorable incitements seem sufficient to keep peer review alive, but insufficient to ensure its quality. The second part of the answer is social dynamics. There is a norm in place stating that one should do one’s fair share of reviews so as to not “free-ride” on others — in this regard, peer review is a common goods problem. While the individual and social norm keeps the system afloat it creates a central system risk in the form of a snowballing effect.

The snowball effect occurs due to the proliferation of free-riding behavior. When individuals believe that others are not fulfilling their obligation to review, this leads to a decrease in motivation to review, perpetuating the belief. Once the snowball starts, it is hard to stop. This shift in perception can rapidly cause a change in social norms, resulting in a large-scale giving up on peer review.

What might trigger the snowball? Obviously, it can arise from academics stopping to review. Frustrations with bad reviews, luck or long wait times might prompt such decisions. However, academics do not need to stop reviewing in order to trigger the snowball. If they increase their individual productivity this will frustrate the system. This is due to multiple reviewers being needed for each manuscript2; typically, 2 to 4, and possibly more if the paper is rejected and resubmitted. We can illustrate the problem assuming each paper needs 3 reviewers. If 100 academics write 1 article each then they must review 3 articles as well; implicit in this process, editors have the challenge of finding the 3 reviewers. If the academics instead publish 4 articles, then editors get busy finding 12 reviewers and academics get busy reviewing 12 manuscripts. Thus, with increased productivity, we will eventually run out of time to review, or editors will fail to scale their recruitment network. In either case, a backlog of unreviewed material piles up which frustrates the academic community and pressures the norm-upholding belief that “everyone else is doing their fair share of reviewing”. Direct evidence for the reviewer bottleneck is found in editors expressing increasing difficulties with recruitment (two Twitter examples 1,2). These difficulties are also manifesting in initiatives where authors now can suggest their own reviewers - a strategy that might be as sensible as letting suspects nominate their own judges.3

The current peer-review system is threatened by bad incentives, fragile norms, and a system that struggles to scale. For this reason, I predict we will see substantial changes to peer review on a 5-year horizon. A prediction that is in line with the journal eLife discarding the old publication format for “reviewed preprints.”

Academia has experienced exponential growth in personnel and article productivity. Productivity is extremely lucrative for commercial publishing and has also become a prestige marker for academics. Thus, their incentives are aligned in favor of a continued increase. The losers in this system are the public, governments, and whoever else relies on the quality of our scientific literature. This is because the central epistemic safeguard, peer review, is struggling to keep up.

What’s the way forward? For now, I recommend this overview of peer review reforms (a pre-print to treat with care!) while I hope to discuss solutions in a future blog post. Lastly, it’s important for me to stress that I am not advocating for less funding of science or a disregard of peer review. My arguments should also not be viewed as support for naïve anti-science movements. Science is far too important for this and that’s why we need to replace Maxwell’s archaic system with incentives and structures that are conducive to large-scale quality science.4

Adam Finnemann is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam where he is affiliated with the Psychological Methods Group and the Centre for Urban Mental Health. His main interests is applying ideas from complexity science to the field of psychology, particularly to study how cities shape our psychological lives.

Stephen Buranyi has written an excellent long-read on the topic which I summarize here.

I owe this argument to a talk between Denny Borsboom and Marjan Bakkers.

See Leo Tiokhin's blog for a discussion

I’d like to thank Karoline Huth, František Bartoš, Lars Harhoff Andersen, and Noah van Dongen for helpful comments on the article