Should Science be Ideological?

It has long been the ideal that science should not be ideological. Here is why it needs to stay that way.

By Lars Harhoff Andersen

The opinion that science should be ideology-free is close to universal among economists and – I suspect – the general public. However, in many other disciplines, it is fashionable to argue that science is always ideological or that the idea of an ideology-free science is ideological itself. In this article, I will attempt to explain the argument behind this view and why I think it is misguided and does fundamental damage to the reputation and prestige of science in the public mind.

What Does it Mean for Science to be Ideological?

One of the major obstacles to understanding the relationship between science and ideology is that it’s unclear what the word “ideology” actually means. Typical of terms used in social science, if you look up ideology, you will be presented with several different, but related definitions.1 Most of the definitions, however, agree that ideology refers to systems of beliefs, especially those related to politics. Socialism and liberalism – as examples – are series of interconnected ideas, both about how the world works, but also about how the world should work – i.e. beliefs about what a just society looks like. It is both a part of Marxist ideology that the income of the rich is taken from the working class and that this is unjust. We might therefore say that ideologies are systems of beliefs about how the world works, interwoven with ideas about how the world should work.

With these definitions of ideology, we can say that a scientific idea is ideological if it’s formed by one or more ideologies – that is, not only by ideas of how the world works but also ideas about how it should work. This also fits neatly with the common use of the term. Normally, if someone says something like “economics is ideological” they do not mean “economics is a system of ideas” (duh), but rather something like “economics is motivated by politics”. This definition also captures why we do not say that the theories of physics constitute ideologies. They might be “systems of beliefs”, but they do not contain considerations on how the physical world ought to be, in the moral sense of the word.2

I think there are fundamentally two views on this question that merits discussion. The first view is that while ideology (along with other biases) sometimes influences science, it is not a fundamental part of science itself, but rather a form of pollution. It might be impossible to avoid completely, but the goal is to keep science as value and ideology-free as possible. The second view is that while science is also an attempt to understand the world (rather than a simple attempt at power), our perspectives of the world are inseparable from ideology and norms. In this understanding, while some perspectives and methods might be more accurate or useful than others, there is no viewpoint outside of ideology. To use an analogy, while the first position is that ideology obscures the vision of science, the second position is that ideology is the glasses we use to see.

Is Social Science Always Built on Ideological Preconceptions?

To investigate the claim that ideology is fundamental, rather than accidental, to social science the argument must be made that we cannot make social science without using the glasses of ideology. If such an argument of necessity cannot be made, we need to fall back to the position that even if ideology often plays a role in science, it can be minimized. I think many of the arguments for the necessity of ideology in social science can be boiled down to three primary categories.

The first and simplest of these arguments claim that it is impossible to understand the world without ideological preconceptions of it. While it is true that we cannot form theories or make empirical investigations without previous conceptions and understandings, the problem with this argument is that it assumes that these preconceptions are necessarily ideological. While many (if not all) people’s understandings of how the world works are interwoven with and influenced by their ideas of justice and politics, this does not mean that it is impossible to disentangle them in a specific context. It might be that people’s ideas about climate change or tax cuts are motivated by their political beliefs (rather than the reverse), but this does not mean that there is no objective truth about the effect of tax cuts or the future of global warming, nor that we cannot investigate them as scientists without referring to political motivations.

Even if we buy into the idea that initial investigations are always built on a foundation of prior ideology, it does not follow that such ideology will become fundamental or permanent in later understandings. For a very long time, it was a deeply held belief among the majority of economists, polling as high as 79% among economists in 1990, that raising the minimum wage would lead to more unemployment among low-wage earners. However, in a seminal paper, that was part of a broader turn towards more empirical stringency in economics, Card and Krueger showed that the opposite might happen as well. Multiple prominent economists objected to the result at the time, in a manner that is hard not to see as ideological, most famously James Buchanan from whom we have this slightly embarrassing quote:

“The inverse relationship between quantity demanded and price is the core proposition in economic science, which embodies the presupposition that human choice behavior is sufficiently rational to allow predictions to be made. Just as no physicist would claim that “water runs uphill,” no self-respecting economist would claim that increases in the minimum wage increase employment. Such a claim, if seriously advanced, becomes equivalent to a denial that there is even minimal scientific content in economics, and that, in consequence, economists can do nothing but write as advocates for ideological interests. Fortunately, only a handful of economists are willing to throw over the teaching of two centuries; we have not yet become a bevy of camp-following whores.”

There is of course still lively debate about the circumstance under which minimum wages lower employment and when it doesn’t, but in general the science of economics saw the data and changed its mind, and in 2021 Card won the Nobel prize.3 Ideology might make scientific change slower than it should be, but if a consistent commitment is made to empirical science all but the most pigheaded people will change their minds.

Finally, as will be important below, the change in ideas did not come from an ideological counterattack from Buchanan’s ideological opponents, but from the slow build-up of empirical evidence. The only person who is warning us to be “mindful of ideology” in this story, is the man trying to protect his own ideology against the data.

Can the Terms of Social Science be Ideology Free?

The second argument for the inseparability of ideology and science is more sophisticated and relates to the role normativity plays in the construction of scientific terms. Consider a term like “democracy”. If someone says, “The United States is not a democracy”, is this a normative or descriptive statement? While the proposition might seem purely descriptive at first glance, the very definition of democracy is hard to disentangle from politics and ethics. Does a democracy require elections? How often? Can the elected officials do anything or is there a limit to majority rule? Should there be freedom of speech? Is hate speech allowed? These questions are partly descriptive (what things help give power to the people?) and partly normative (what kinds of self-determination are most important?). It turns out that many of the terms we use in social science, such as “democracy”, “welfare”, and “development”, have definitions referring to ethical considerations. If this is the case, it seems to follow that any discussion of democracy, as well as other terms like it, will both (at least implicitly) be normative and descriptive– and thereby ideological.

While I think the above makes a stronger argument against the idea of ideology-free science, I think the conclusion should not be brought too far. Firstly, while it is true that many terms we use in social science have implicit normative elements, it does not follow that they need to. We could, for example, imagine a definition of democracy that removes the normative elements by defining it as systems with representative governments and free speech, and then use this definition value neutrally to also cover societies that we do not feel live up to any specific ethical promises. I think this is what actually happens in most cases when social scientists (of the empirical kind) talk about things like development and democracy.

Secondly, since many of these problems arise from the use of broad terms like “development”, “democracy” or “welfare”, we can potentially solve the problem by referring to more narrow terms like, “wages”, “votes” or “consumption”, as suggested in this insightful article.

Finally, I think it is also worth reflecting on the degree to which this actually matters. In the end, social science is built around questions that the scientists and the public at large want to know about the world. Does democracy cause growth? Does Facebook lead to polarization? How do we avoid war? In order to answer if the ideological nature of terms like “democracy” make the science ideological we need to ask ourselves: Would the answer to a given question have been different if we had used another definition of democracy? In most cases, it wouldn’t. We might argue over whether Botswana is more democratic than Portugal or maybe Honduras and Mexico, but no sensible person would argue that China is more democratic than the US or Saudi Arabia more than Chile. In the cases where our definition actually matters - say in the case of Hungary – what happens (when things go well) is that we start disentangling the terms and speak about liberalism and majoritarianism. A good rule of thumb is therefore: If changing your definition does not change the answer, then the definition is of little importance. If value-laden definitions do not change the answers to important questions in practice, it is hard to argue that the terms are fundamentally ideological in any way that matters.

Does social science ever ask unideological questions?

A third argument, related to the second, is that even if the terms themselves are neutral in a strict definitional sense, ideology influences science through the researchers’ choice of questions. It is trivial that the questions we ask reflect what we care about. We study poverty, wealth, and democracy in social science as well as fuel efficiency and speed in engineering because these things in one way or another matter to us, personally, ethically, or ideologically. The interesting question is whether this choice of scientific direction influences the answers we give to fundamental questions, even if we attempt to answer all questions without bias.

An interesting example of this problem in practice is the discussion of the relative merits of tax cuts and public spending.4 Because many studies have been done on the effects of tax cuts on labor supply, the effects of these are included in growth projections, but because fewer studies have been made on the effects of public childcare on the same, the effects of these are not counted. Thus, even if we assume that none of the relevant studies of tax cuts are biased, the very fact that there are more of them will mean that the positive effects of tax cuts are seen as more “scientific” than the negative effects (in the form of fewer public services). We can thereby have a situation where each specific study is done without bias, but the choice of study question influences which conclusions we end up drawing as a society. Defining what questions are asked can define, at least in some circumstances, what answer is given to broader questions.

This is not only, in my estimation, the biggest source of scientific ideology-bias, but also the best case for the fundamental, rather than accidental, account of science as ideological. If the questions we ask in science bias our results, or the understanding of the broader public, we can’t fix this by only choosing “neutral questions”, because any question focuses on a normatively selected part of the world.

Though I think this poses a serious objection to the idea of ideology-free science in a strict sense, I think it is very easy to overstate the issue. While it might be true that our choice of question can influence our understanding of a subject, this is partly because we tend to confuse a lack of knowledge with a lack of effect. In the case of weighing tax cuts against public services, the answer is that we shouldn’t weigh down the importance of the second just because we know more about the first. It is simply a logical error to assume that the effect of something is zero, just because we haven’t investigated it, and the correct course of action is that politicians use their personal judgment in cases where science has not yet come up with clear answers. While the choice of questions is fundamentally ideological, there is no reason that their answers need to be as long as we are clearheaded in understanding how they play into broader societal questions and our understanding of them.

In sum, while the idea of a fundamentally ideological science poses some interesting questions, in the end, we cannot call science fundamentally ideological unless the big questions it attempts to answer will be biased by logical necessity. Said slightly differently, if it is possible to eliminate a bias, we can think of it as contamination, whether it should be viewed as such from a metaphysical standpoint or not. While it might be hard to think of a “disinterested question” it is also hard to think of an ideologically motivated question, that we cannot attempt to give a non-ideological answer.

How do we Minimize Ideological Bias in Social Science?

While the idea that we should try to minimize bias in social science is still the most prevalent, I think that even among scientists who subscribe to this view, there are some ideas about how it should be done that do more harm than good. One such idea is that because we are all biased by our ideology, we should constantly see science through the lens of ideology to counterbalance our biases. This argument often comes in the form of warning scientists to “beware of our ideological assumptions” and the “narratives we are helping”. The fundamental idea is that since we all have biases we should not aim for “neutrality” or “disinterest”, but rather to counterbalance the ideological biases we have. The problem with this approach is that in practice this is never turned against our own biases and ideological preconceptions, but instead against results that do not fit our own political agendas. While the argument might have a shallow veneer of humility it barely hides the arrogance from which it was born.

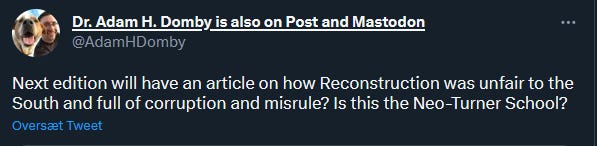

I have never attended a seminar where a researcher used the fact that his results confirmed his epistemic priors or ethical values as an argument against his hypothesis, but I have many times heard people criticizing other people’s research for being “ideologically problematic” because it did not fit with what they wanted to be true.5 A illustrative example of this came when some economist had published a paper supporting the so-called “Frontier Thesis”, which led to an explosion of angry historians on Twitter. Though some had scientific objections to the paper, the vast majority of the historians who formed some arguments against the paper argued that the problem was with the ideological implications.

It is not my errand to adjudicate whether the historians (who had arguments) or the economist are right in this specific case. Rather, I want to point out that the idea of being aware of “political bias” was raised because a certain result didn’t conform with the ideology of people making the critique, not because it did. A similar thing occurred a few years ago when a paper showed that it could be (on some measures) beneficial for children if their siblings and parents were sent to jail. Many academics objected to the paper, some going so far as to imply racist motivations. Once again the reason it led to such an uproar was not that it followed the orthodoxy, but that it went against it.

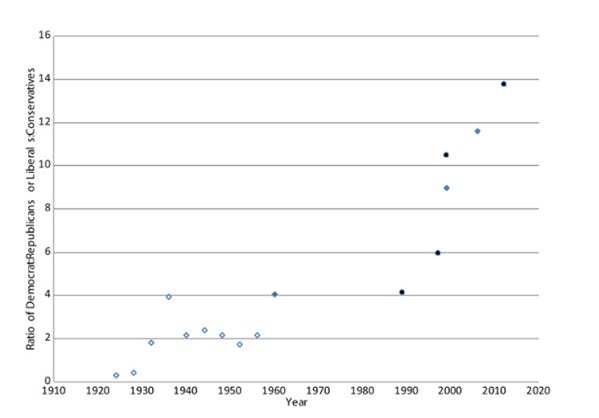

In the same vein, it was Buchanan who accused Card of “ideological interest” in order to protect the orthodoxy, not the other way around. Being aware of bias is always something other people have to do, never yourself, and this is why it is a useless tool for avoiding political bias. In the present day, almost all academic research is done by people with very similar worldviews to one another and in the US there are around 14 liberals for every conservative professor. If we accept the idea that we can criticize a piece of research simply because it “fits a narrative” or is “ideological”, I have trouble seeing a world where this does not simply become a carte blanche for suppressing dissenting ideas.6 If we want to get rid of ideology, we should not fight fire with fire, but stride towards objective, epistemic standards as an equal opportunity champion against ideological bias.

Though we have seen many instances of ideological influences above, I argued that by leaning into objectivity, be it in methodology or conceptual analysis, this influence can in most cases be mitigated. The fact that we will never succeed in making science perfectly objective does not mean that we should not try, but that we need to try harder. If you suspect that the ideology of scientists means that some questions are valued over others, which is very likely true, then attempt to answer the questions that other people are not willing to answer!

In my own field of economics, there has been a strong ideological bias but because there was also a commitment to empirical positivism, the field eventually started throwing out its most ideologically influenced ideas, when the data could no longer be ignored as we saw with the minimum wage, RBC models, and behavioral economics. A commitment to dry empiricism slowly destroyed the bad ideas and gave dissenting economists a path from notoriety to Nobel, though the path was often longer than it should have been and many ideas are still waiting to go extinct.

Thus, our goal as scientists should be to answer questions with as little regard to what the answers might entail as possible. Of course, people also use positivist language to dismiss scientific results that they do not like, but the fundamental difference is that if one is attacked for lack of scientific rigor one can (in contrast to charges of “political bias”) defend oneself on scientific grounds. Don’t say you don’t like the conclusion, say how the methodology was bad. This might not remove bias completely, but it might level the playing field and give ideologically inconvenient ideas a fighting chance.

Though many scientists like to pretend otherwise, academia is still broadly respected and to the degree that it is not, such disrespect is driven by the fear that what we as academics do is driven by our own politics and ideology, not that we are insufficiently mindful of politics. When researchers argue that science is just an extension of ideology, they are hurting the credibility of science. With certain social scientists, their attitude towards the idea of ideological science seems to bring our glee, rather than concern. What they seem to hear is not that their knowledge is biased, but that their bias is science. If all science is ideological, it might as well be their ideology. Thereby, the idea becomes a permission slip rather than a warning sign. It is a bit like a doctor unable to hold back a smile as he tells you that all doctors lose patients sometimes.

It might be tempting to use one’s academic prestige to further political goals, but this is impossible to do without undermining the very same. Scientists have been given the mandate to find the truth, but the public still retains the privilege of determining the good. It is the task of the scientist to tell the public what they would believe had they his knowledge, not what they should they believe had they his moral character.

Lars Harhoff Andersen is an editor and writer at Unreasonable Doubt, where he writes about Culture, Politics, and Philosophy. Lars is a Ph.D. fellow at the Department of Economics at the University of Copenhagen where his research centers on Economic History and the impact of culture on societal development. Lars is also the host of the (Danish language) podcast Historien Fortsætter.

If you liked this article, you might also like our post on feminism and economics.

As I discuss in a previous post the reason that such terms are vague is fundamentally that the phenomenon itself is vague and amorphous.

Here it is important to note the difference between a theory that is caused by ideology and one that is imbued with ideology. When Isaac Newton formulated his laws, he was, partly, motivated by his personal desire to show the beauty of God’s creation and we might therefore say that the “cause” of his theory was ideological. However, as long as the content of his theory was determined by epistemological considerations and not ideological ones, we might still say that the theory is not ideological. This is an important point because it means that we cannot dismiss thinkers simply from the fact that they have political opinions unless this ends up coloring their judgment.

For more on Card, Kruger, and the slow turn away from the economic orthodoxy on the minimum wage see this blog post from Noah Smith.

This is one of the examples discussed by Emma Holten in her lecture series discussed in a previous article.

It turns out that it is never really “more complicated than that” when you agree with the results. Go figure.

This is not to say that diversity, on race, class, ideology, and so on, might not be a good thing. As Matthew Yglesias points out in this blog post the larger degree of ideological diversity in Economics might be why it tends to produce better research, and outcompete other fields on its own turf.