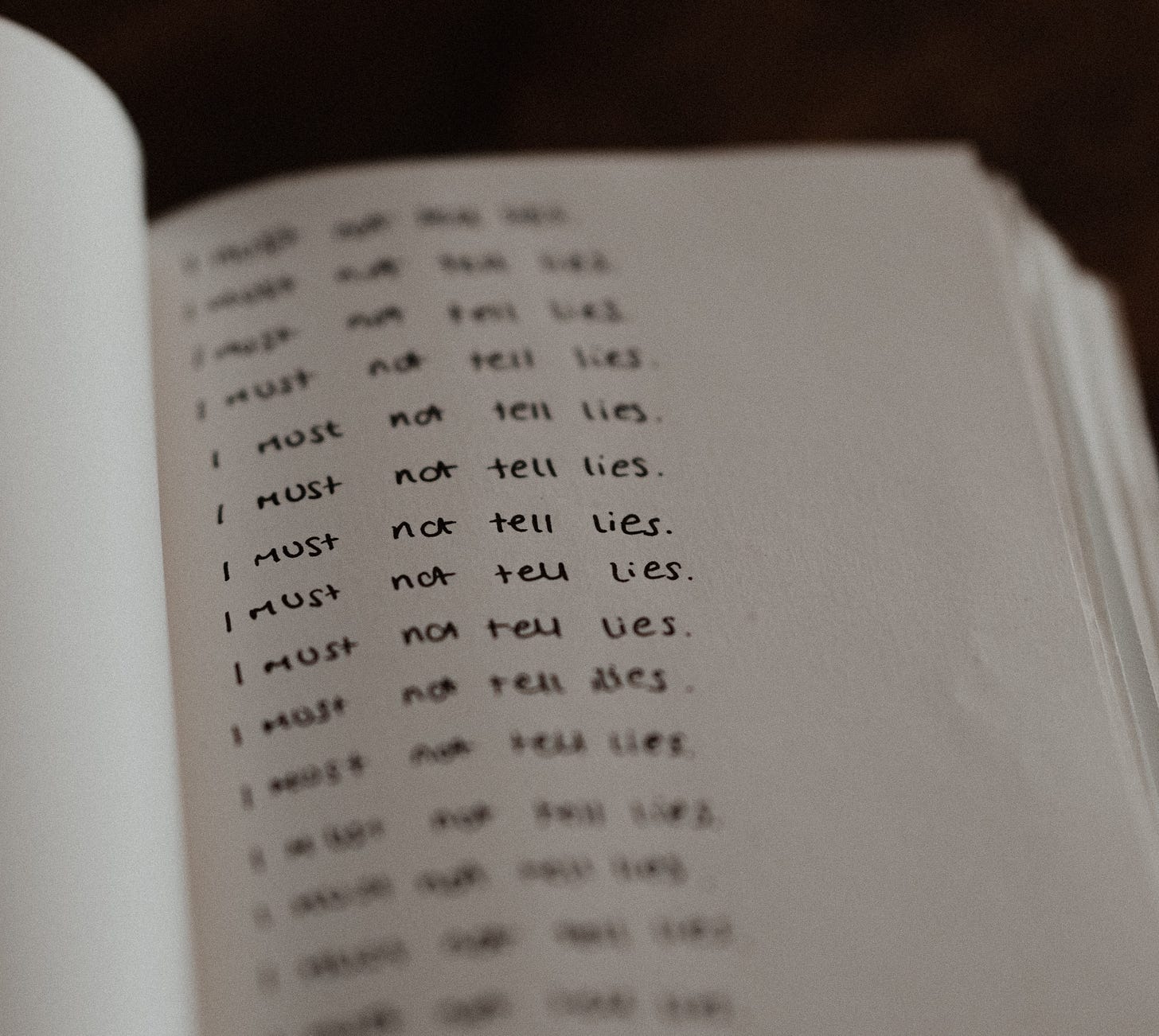

The Case Against Lying

In the public sphere, there is a growing set of defenses of casual lying. This post argues that acceptance of even the most well-intended lies might cost us more than we imagine.

By Lars Harhoff Andersen

In a recent article in the New Yorker, it was revealed that American comedian Hasan Minhaj had made up many of the experiences of racism in the United States that he had built his career around sharing. Interestingly, while Hasan acknowledged that he had said these things knowing that they were untrue, he argued that they were not lies, but rather “Emotional Truths”.

While lying is obviously nothing new, something is interesting in the fact that people, like Hasan, who get caught lying try to pass it off as somehow politically or emotionally profound, to have a loose relationship to the truth. But, lying, even in the service of good, can have more far-reaching consequences than we tend to imagine. Though it might be expedient at times, lying risks spreading mistrust and damages our hold on the truth, potentially for a much longer time than we imagine.

Emotional Truth

The New Yorker Article about Minhaj is an interesting one because he is remarkably honest about his dishonesty. Defending himself, he seems to be saying the quiet part out loud. Minhaj has claimed that his mosque was infiltrated by the FBI, which led to him being handled violently by the police, and that his daughter was sent to the hospital because someone sent them a white powder in the mail. All of this (and much more) turned out to be a complete fabrication.

When confronted with this Minhaj neither denies what he said was untrue nor apologizes for lying. Instead, he argues that while he knowingly said things that he knew to be untrue, these were in the service of a higher, “emotional” truth. As he says in the interview, “the emotional truth is first. The factual truth is secondary”. Being compared to the serial liar and US Congressman George Santos, he defends himself by saying that while Santos's lies were pointless, his own was in the service of something bigger. His argument seems to be that because he is lying to convince his audience of a larger truth – that Indian Americans experience racism in the United States - it cannot be said to be dishonest, even when it is factually untrue.

The idea that lying in service of a higher truth is morally justified is often found in conjunction with the idea that stating a fact that can be used against such a higher truth is immoral. In a recent episode of the Majority Report, host Sam Seder had journalist Jesse Singal on his program to discuss the value of the latter’s reporting gender detransition.1 In the clip Seder argues that there are arguments that are “philosophically” (and thus presumably factually) correct, but which should not be made because it can be used as an argument against a higher truth.

The ideas of Seder and Minhaj are not separate, but rather two sides of the same epistemological coin. The implicit assumption in both arguments is that we already know the higher truths and that the function of facts is therefore purely rhetorical. They are meant to convince and exemplify the things we already know, not to explore the world from the ground up. We do not need to speak truthfully about trivial facts, because we already know the higher truths. In this conception of honesty saying something (emotionally) true means saying something that will make people have a truer conception of the world as such. You are speaking the truth if you are giving people correct opinions and you are dishonest if you do not.2

But this is an incredibly dangerous way of thinking. Not only does it assume that we do not need to have our present beliefs refined by new facts, but it also assumes that once we have released misinformation into the world, we will be able to control or predict its consequences.

From Russia with lies.

As depicted in the brilliant show Chernobyl on HBO, when the 4th reactor at the Chernobyl plant exploded the state attempted to keep it quiet. Exposing the scale of the disaster would make the regime seem incompetent and feeble, both in the eyes of its people and in the eyes of Western leaders. To protect the regime, it was deemed necessary to sweep the consequences under the rug. First, it was attempted to hide that a disaster had occurred, and then the official limits for acceptable doses of radiation were changed to lower the number of people potentially affected negatively by the explosion.

But the lies went deeper than just the cover-up. The entire apparatus of the Soviet system was built around making the regime appear competent. The system therefore methodically covered up facts deemed dangerous to the larger narrative of Soviet greatness. Thus, it was discovered as early as 1975 that the graphite control rod tips that ended up leading to the disaster at Chernobyl could cause a meltdown, but instead of being acted on it was hushed up.

The paradox of all this is of course that the lies the system told to protect the regime from collapse, might very well have been the very thing that brought it down. The Chernobyl disaster eventually grew to a level that was impossible to hide, and it ended up exposing the immoral and incompetent soviet system, not only to the West, but to its own citizens. According to the then leader of the country Mikhail Gorbachev, this is what eventually led to the fall of the regime.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, there was a general sense of surprise that the Russian army performed as poorly as it did. Not only this, but many of the strategies pursued seemed strange and incoherent. It might be that the culprit, once again, is lying. It has however been argued that fault is once again lying. A dictatorial system of government has the fundamental flaw that it is dangerous to disagree with the dictator. Therefore, Putin’s advisors are unlikely to do so. It is likely that Putin was lied to about his ability to win the war, by his own advisors, giving him a skewed picture of the probability of victory. But even more so, the years of being exposed to his own propaganda about the glorious past, present, and future of the Russian empire, might have led him to fundamentally misunderstand his own country and its relationship to its neighbors.

A lie originally told to support something believed to be true might go around and become part of the justification for believing it in the first place It will often seem to us that we can control the consequences of our lies, and in the short run, we very well might be able to. But over time lies will not just spread to other people but might very well end up destroying our ability to make sense of the world. When Mihnaj lies about his personal experiences he defends it by pointing to the larger emotional truth of American racism, but how does he know that his awareness of this comes from reality and not other people like him making up stories to serve a narrative? And if his “emotional truths” are accurate, how does he know that lying will not convince people that they are not?

Fighting Fire with Fire

Though the problem of dishonesty is more pronounced in dictatorships and among people with extreme beliefs, the idea of the noble lie is by no means limited to those on the political fringes. In fact, in the relative mainstream, I think there has been a growing acceptance of dishonesty as a method for political communication.

For just as long as there have been discussions about climate change there has been climate denialism, both in the form of denying the changes themselves and in the form of denying that they are (primarily) driven by human actions. Climate change is among the most pressing problems in the world today and climate denialism has been both a tool of personal enrichment and the opinion of choice for useful idiots. Presumably, as an attempt to fight fire with fire, there is however also a lot of misinformation about climate science on the side of climate advocates. Politicians like AOC have said that the world will end in 2030 if we do not do something now (2019) about climate change. Not only is this false, but it gives charlatans on the other side the ability to make a plausible case against trusting the establishment's view on climate change.3

The damage of this kind of hyperbole has become so destructive for the fight against climate change that the newly appointed head of IPCC felt the need to go out and warn against climate doomerism:

"If you constantly communicate the message that we are all doomed to extinction, then that paralyzes people and prevents them from taking the necessary steps to get a grip on climate change. The world won’t end if it warms by more than 1.5 degrees. It will however be a more dangerous world.4

A similar dynamic played out during the discussions about COVID-19 and what measures were appropriate to fight the virus. At the beginning of the pandemic, the American health authorities feared that they might end up with a shortage of medical protective gear if public demand became too high. Therefore, they lied and said it was not effective. This was not the result of some dark conspiracy. It was because the authorities thought that a “noble lie” was in the best interest of the public. They might have been right - but stating that masks didn’t work also sent another message: The government is willing to lie to you about your health.

The incredibly fast invention and distribution of vaccines against COVID-19 is estimated to have saved 10s of millions of lives and is a triumph of modern medicine. However, across the world there is widespread distrust of vaccines and for this reason, some people don’t get vaccinated. In a study of vaccine uptake in South Dakota, researchers found that people who showed lower trust in doctors and the government were less likely to use the vaccine. The vaccine debate likewise is polarized across the political spectrum in the US and a recent working paper shows that while there was little difference in mortality across Republicans and Democrats from COVID before the vaccines, it is now substantial.

It is of course not Fauci, but the people spreading anti-vaccine propaganda out of cynicism or stupidity, who are the main villains of the story. But there are institutions, from health agencies to universities, that have great power in determining public opinion. If we are in such an institution, we should not only care about our ability to influence public opinion now but also think about how our contributions to science and the public discourse will affect the credibility of our institutions in decades and centuries to come.

A quick lie can have consequences for a very long time.

The Long-Run Effects of Bullshit

Vaccine hesitancy is not a new phenomenon but goes all the way back to their invention. It is also not a novel phenomenon that vaccine hesitancy is associated with political divides. One of the best examples of this is the stark divide in vaccine uptake between East and West Germany, presumably showing a negative legacy of communism of modern-day trust. However, a new study by Andreas Link and Christine Binzel, argues that something else might be going on as well.

It turns out that around half of the difference between East and West can be traced back to the so-called “naturopathic movement” in the 19th century, long before the split between East and West. Naturopathy is a form of alternative medicine promoting the idea of the self-healing body and is skeptical of drugs, vaccines, and surgery. It is also complete bullshit. Neither in the 19th century - nor today- did they rely on rigorous scientific testing to come to their conclusions, but rather built their practices on a vague sense of healthy nature, as opposed to a corrupt modernity. And, if the paper is to be believed, the wave of naturopathic bullshit that washed over Germany in the 19th century is still killing people (my words) 150 years later. It seems that bullshit might be very long-lived indeed.

It is important to note that at the time there might have been real benefits to the ideas of naturopathy as well. Like other pseudoscientific types of healing, like acupuncture, chiropractic, or crystal healing, naturopathy might very well occasionally or even often have given good advice. Medical science was in its infancy in the 19th century, and in many cases, it was probably better to take a cold shower than to subject oneself to what passed as medicine at the time. Likewise, if naturopaths advised people to exercise this would have made them healthier, even if the naturopath’s ideas about why exercise works might have been bullshit. But, just as is the case now, saying that the medical establishment is incompetent and corrupt might have had strong implications outside of the narrow question of exercise or medical treatment.

Spiders in the Web of Knowledge

If one is generous towards Mihnaj the lies he told about his life were to convince people that ethnic minorities experience hardships that need to be addressed. If one is less generous his lies were an attempt to boost his career through self-aggrandizing. Now as the truth is coming out, I suspect that his lies have hurt both causes.

The problem with lying for a good cause is fundamentally that whenever we are dishonest about one thing we are in effect dishonest about everything. Knowledge is not a long list of facts, but rather a vast interconnected web of ideas and facts supporting each other. If you change one thing, you inevitably change something else in the system as well. If you believe that vaccines do not work, you also implicitly believe that doctors are incompetent or dishonest about their efficacy or safety. Now if you are young and healthy, getting a COVID vaccine is not a matter of life and death, but the idea that doctors are incompetent or dishonest might very well be. When your doctor years later urges you to get chemotherapy instead of crystal healing are you not more likely to ignore him? Moreover, if the government, media, and universities are lying to you about vaccines, what else are they lying to you about? Did Joe Biden really win the election? Is Climate change a hoax? Did we really land on the moon? Any lie or lazy untruth you believe will carry with it an implicit story of those who disagree with you and how the world works, which is likely to take on a life of its own.

Toward the end of the show Chernobyl, the main character gives a speech about the consequences of lying which includes the following quote:

"When the truth offends, we lie and lie until we can no longer remember it is even there, but it is still there. Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later, that debt is paid."

Minhaj has incurred a debt to the truth. Let us hope that he will be the one to pay it.

Lars Harhoff Andersen is an editor and writer at Unreasonable Doubt, where he writes about Culture, Politics, and Philosophy. Lars is a Ph.D. fellow at the Department of Economics at the University of Copenhagen where his research centers on Economic History and the impact of culture on societal development. Lars is also the host of the (Danish language) podcast Historien Fortsætter.

If you liked this article, you might also like our post on Ideology and Science.

I was not able to find a copy of the episode directly on the Majority Report, but I was able to find this “reaction video” from the political Twitch streamer Destiny.

This attitude is more common than one should think. I once had an acquaintance who studied misinformation as an academic researcher, but who was also involved in youth politics. In his function as a political activist, he had shared a meme with some misinformation about the economic status of women. Though he acknowledged that the information he had shared was wrong he declined to take it down, giving me the reason that though the specifics in the meme were wrong, it was still true that women had worse positions in society than men. With Friends like these, I think the truth does not need enemies.

This example was taken from this article, which also gives other examples of centrist and progressive misinformation.

Quote taken from this article.

Just a heads up, his last name is spelled "Seder". Nice article though!