The Paradoxes of the Tolerant

How the Intolerant Tolerants Misuse the Philosophy of Popper to Limit the Freedom of Speech

By Lasse Jacobsen

In the last couple of years subjects like ‘tolerance’ and ‘intolerance’ have been acting as a fierce arena for debate. When Trump came into office a great debate regarding the limits of tolerance was ignited, and in my native Denmark some on the left have argued that politicians from the rightwing party “Nye Borgerlige” shouldn’t be school teachers because of their political views .

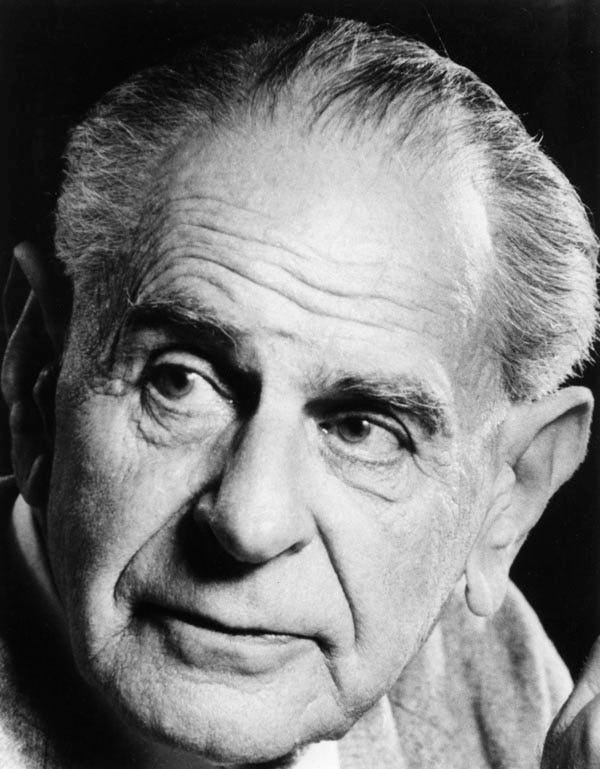

Many people bring about the notion that the liberty of the intolerant should be limited with reference to Karl Poppers Paradox of Tolerance, often using the following cartoon:

In this post, I will argue that the argument is based on a misunderstanding of Karl Poppers intentions with the paradox and where we as a society should place the limits of toleration.

The Context and the Explanation

While the paradox of tolerance has been invoked many times recently, Popper actually, doesn’t say much about it in his works. It is only mentioned once in a footnote in “The Open Society and its Enemies”, in a chapter dealing with how an open society avoid such paradoxes. The fact that the paradox is only mentioned in a footnote to a 726 page book should in itself be a clue about the importance of the paradox to Popper.

The footnote goes like this:

“Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.—In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise (highlighted by Lasse Jacobsen). But we should claim the right to suppress them, if necessary, even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.”

As I have highlighted, Popper himself only thinks that society should suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies, if they can’t be kept in check by other means. Here context matters: ‘The open societies and its enemies’ was written during World War II when totalitarian ideas were dominating the political landscape. It was a response to these ideologies Popper and ideas of Plato, Hegel and Marx, from which he believed they grew out of.

The book itself is a manifesto as what not to include if you aim towards an open society with free exchange of ideas. The open society according to Popper can only be achieved through liberal democracy, which provides an institutional mechanism for reform and leadership change without the need for revolution, violence and so on. The central idea of the book is, that it is through debate and the free exchange of ideas in a liberal democracy that one is given the best chance of avoiding violations and intolerance. The context of chapter 7, in which the paradox is presented is to use different paradoxes (like the paradox of tolerance) to disproof the notion that such paradoxes can be used as a rational for autocracies, like the one proposed by Plato. The whole mantra for Popper is that if a society is built upon liberal democracies with a well-functioning liberal constitution, then the paradox can be avoided.

Toleration and the Common Interest and Toleration of the Intolerant

Though the interpretation of Popper in the discourse thus misses the point, the original problem remains. When are ideas dangerous and intolerant enough to be censored, and when should they be fought with words? I suggested we look to the another of the great liberal thinkers of the 20th century.

In the book “A Theory of Justice”1 John Rawls describes the duty of the state regarding toleration and to what degree the state can interfere in the lives of those who hold totalitarian opinions. Rawls writes that the state “does not concern itself with philosophical and religious doctrine but regulates individuals’ pursuit of their moral and spiritual interests in accordance with principles to which they themselves would agree in an initial situation of equality.” For Rawls the state shouldn’t concern itself with what people are thinking and believing, only instead only with regulating people’s behavior in accordance with the “public order”:

“The government’s right to maintain public order and security is an enabling right, a right which the government must have if it is to carry out its duty of impartially supporting the conditions necessary for everyone’s pursuit of his interests and living up to his obligations as he understands them.”

For Rawls it is thus ‘ok’ for the state occasionally to interfere in the conscience of its citizens, but only when “there is a reasonable expectation that not doing so will damage the public order which the government should maintain. This expectation must be based on evidence and ways of reasoning acceptable to all.”. This means that according to Rawls shutting down speech should stem from arguments based on the speech and its damaging nature to the public order, and not from a negative judgement of the values expressed in said speech.

But what constitutes “based on evidence and ways of reasoning acceptable to all”? According to Rawls we can only answer this question truthfully behind the veil of ignorance2. Because only under the veil the answer would represent an agreement to limit liberty only by reference to a common knowledge and understanding of the world.

With both Popper and Rawls, the limitation of liberty is justified only when it is necessary for liberty itself, to prevent an invasion of freedom that would be still worse. Thus, the parties in the constitutional convention, must choose a constitution that guarantees an equal liberty of conscience regulated solely by forms of argument generally accepted, and “limited only when such argument establishes a reasonably certain interference with the essentials of public order.”. When Rawls writes about the constitution regarding toleration it very much resembles the writings of Poppers Open Society, and how he placed his faith on the liberal democracy and the institutions it compasses.

The link to Popper is further cemented when Rawls discusses how the citizens of a well-ordered society that accepts his principles should react if an intolerant sect come to exist. According to Rawls, if the constitution is just the citizens have a natural duty to uphold it, and this duty is not terminated just because others “are disposed to act unjustly”. Instead, a more stringent condition is required:

“There must be some considerable risks to our own legitimate interests. Thus, just citizens should strive to preserve the constitution with all its equal liberties as long as liberty itself and their own freedom are not in danger. […] But when the constitution itself is secure, there is no reason to deny freedom to the intolerant”.

If the constitution which secures liberty and equality is secured, there is no reason to deny freedom to the intolerant. Not only is this a plausible solution to poppers paradox, but it is one in the spirit of the man himself! The freedom of the intolerant should only be limited if the people holding totalitarian beliefs can no longer be “kept in check”, in the words of Popper, or is a danger to the public order, in the words of Rawls. And the only legitimate way of limiting the liberties of the intolerant is if it has been shown through logic and reasoning acceptable to all that not doing so will endanger the public order.

There is no denying that Rawls is in favor of a liberal democracy guided by constitutional rules, when he evaluates whether or not to limit the liberty of the intolerant. And perhaps this is the lesser of the evils considering the paradox of tolerance. Because wanting to limit the freedom of the intolerant constitutes a paradox in itself: wanting to limit the freedom of the intolerant is in itself intolerant, and therefore those who wish to do so should actually have their freedom limited as well.

So perhaps a constitutional rule based upon liberal values and liberal democracy is the best solution. Such a constitution should be guided by objective and general standards for when the public order is at risk and it should be guided by principles which almost all citizens could agree upon. Referring back to the intro, neither Popper nor Rawls would accept to limit the freedom (e.g. say that the intolerant couldn’t teach school students) of the intolerant because they didn’t share their values. Because the free exchange of ideas (Poppers Open Society) is the backbone of preventing hostile takeovers in a liberal democracy, both Popper and Rawls are willing to go to great length to prevent limitations in the freedom of the intolerants.

Lasse Jacobsen is a political scientist working in the field of economics, data management etc. He also writes for the online magazine Raeson.dk.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Revised Edition. Harvard University Press, 1999 Chapter 34 and chapter 35

The Veil of Ignorance (or” The original position”) is a thought experiment which deals with the guiding principles of a society. If you were covered with a “veil of ignorance” which meant that you had no prior knowledge about what position you had in the society, which principles would then be your guiding principles? Rawls himself concludes, that people would mutually agree on the following guiding principles: 1. Each citizen is guaranteed a fully adequate scheme of basic liberties, which is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all others. 2. Social and economic inequalities must satisfy two conditions: a. to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged (the difference principle) b. attached to positions and offices open to all.